Loss is a universal experience; it connects us all. Loss can be felt through bereavement, loss of a relationship, loss of hopes, dreams, or loss of a job for example. Loss is part of life; we experience it from the moment we are born. Loss in this article will refer to the many types of losses not only the loss of a loved one.

The term bereavement refers to an event that occurs; grief is the conflicting feelings caused by the end of a familiar pattern of behaviour (James & Friedman, 2009, p. 9). Its immediate reactions can include feelings of anxiety, sadness, anger, changes in sleep or appetite, and lack of interest (Bonanno & Kaltman, 2001). For this article mourning will be seen as the public face of grief. People can react differently depending on cultural influences. Grieving is the process, feeling or a state and often more private (Wilson, 2014).

Grief can bring about wide-ranging emotions and there may be a feeling of overwhelm. It is often natural to feel a physical reaction to the loss of someone or something. Loss can be felt as a yearning or longing to be with the deceased person again, often there are feelings of sadness, sorrow, and numbness. Life can lose its meaning and there can be a feeling of how things should be. There can be secondary losses such as loss of plans for a future together. Anger and frustration can also be present, a feeling of being left by your loved one or anger at those around you who may have expectations of how you should be behaving.

Initially, grief can feel intense, like close waves hitting you one after the other. Reminders of the person you have lost can trigger a wave. These waves space out over time as you begin to process your loss. As time goes on you will experience firsts: first birthday, anniversary, and holiday for example. The absence of your loved one will be felt on these dates and will trigger the waves of grief again. Worry over how to cope or financial concerns can be intertwined with your grief, washing over you like waves. These feelings both physical and emotional are all part of the process of grieving. A process whereby you come to terms with your loss and work out how you can come to be in a world that feels radically changed. These feelings are normal.

Examples of Losses:

· Divorce

· Miscarriage/Perinatal Loss

· Separation/Divorce

· Retirement

· Redundancy

· Emigration

· Loss of plans for the future – IVF/Infertility

· Illness/changes in relationship

· Pet loss

· Surgical loss

Not all Losses are the Same

Not all loss will affect people in the same way. The circumstances around the loss can affect their grief namely:

1. Was the loss expected or sudden?

2. Was the death because of a long illness? People often report anticipatory grief while the person is still alive.

3. Was the loss sudden, traumatic, violent, or by suicide? In these circumstances, there are often layers of shock and disbelief as your mind works to understand what has happened.

What was the relationship like to the deceased?

The health of your relationship with the deceased and the role the person played in your life can impact how you grieve. The relationship you had and your feelings around them, while they were alive, can also impact how you grieve for them.

Regret and Guilt

It is usual to feel regret and guilt when someone you love dies. You might remember things you would have liked to have done or things you said that you regret. Usually, these issues resolve over time and people find a way of coming to terms with the emotions however, some people can get stuck. They can feel like they are on a loop, and this can be distressing and hinder the grief process. It can be helpful to write down the regrets and try to look at the guilt or regret with kindness and compassion. These regrets are not the whole of your relationship. Try and see if you can look at them with perspective and kindness as though you were talking to a sibling or friend.

Compassion

What stage of life are you at? Do you have space to grieve or are you caring for others? Are you in a busy job? Remember it is always ok to let other people know what you need and when you might like to talk, not talk, or be distracted. You may not know. Whatever you are feeling is ok. Learning to show compassion to yourself as you grieve can help. Being kind and understanding and knowing there is no right or wrong way to grieve, no linear stages and no shoulds can help as you navigate the journey.

Support Systems

Have you a support system that allows for your grief or is it shut down?

Friends and family will want to be supportive, but they may also feel uncomfortable with your grief, find it difficult to talk, or even avoid you.

Conversely, others will want to fix things and expect you to feel better before you are ready. All these reactions impact on how you are feeling.

Grief Models in Therapy

Grief can be like a wound, if you tend to the wound, it has a chance to heal there is a process to healing that is unique to everyone. It can be painful and often there can be a feeling of it being too much. In therapy, certain models can facilitate working with bereavement. They are:

1. Meaning Making Theory: The Meaning of Reconstruction and Loss Framework (MRL) was developed by Gillies and Neimeyer. Reconstruction here refers to processing the loss in terms of sense-making, benefit-finding, and identity change. This can create new meaning for the bereaved person. There is then a process of healing and meaning-making (Gillies & Neimeyer, 2006).

2. Relearning the world: The work of Thomas Attig focuses on adapting to the world following a loss and bereavement and is linked with meaning-making theory. It is in a sense relearning how to be in the world and creating a lasting love for the deceased (Attig, 2001).

3. Assumptive World theory: Colin Murray Parkes’ theory of grief is a further development of attachment theory, specifically developed for the treatment of grief and bereavement. This was a model based on the idea that life can be taken for granted until something changes. The Assumptive World of the bereaved is altered. A psycho-social change threatens their sense of security and causes stress. Therapy in this case involves adapting to these changes and allowing them to be recognised. This theory was also developed by Ronnie Janoff-Bulman about traumatic loss (Janoff-Bulman, 1992; Wilson, 2014; Worden, 2010).

4. Continuing Bonds theory: This theory proposes that to integrate the loss of someone close, those bereaved do not let go, rather a bond is formed to symbolise the closeness and to provide comfort. This is a process particular to each individual and allows the bereaved to move on into their future without the physical presence of their loved one aided by constructing these symbolic bonds (Klass et al., 2014).

5. Dual Process Model: In Stroebe and Schut’s dual-process model (1999) there is a focus on loss and separation on the one hand and the development or resourcing of the bereaved on the other (Stroebe & Schut, 1999). There is an immersion in the grief that can also include periods of avoidance or distraction. This theory holds that these periods of distraction are useful (Stroebe & Schut, 2006; Stroebe & Schut, 1999).

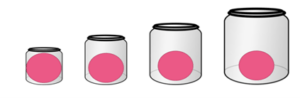

Growing Around Grief – Dr Lois Tonkin

A helpful metaphor for grief was developed by Dr Lois Tonkin. Dr. Tonkin proposed that grief doesn’t disappear, rather people grow around the grief over time. Looking at the diagram the circle inside the jar doesn’t get smaller as time goes on, the jar (your life) grows bigger. There will be new experiences in your life when hopefully you start to reconnect with family and friends and begin to experience moments of joy and happiness. These experiences will accumulate, and the jar (your life) will grow bigger. The grief remains but doesn’t dominate all your life. You carry your grief with you as you continue to live and experience life.

Working through Grief

There are many things that you can do for yourself that will help you to work through your grief. Rituals help you to honour and remember your loved one. Cultures have their own rituals however you can also create rituals of your own for example:

· Planting a tree

· Holding a memorial service or quiet remembrance at a meaningful place for the deceased

· Remembering anniversaries and birthdays as a way of honouring the loved one

· Making a memory box

· Creating a piece of jewelry to wear that is connected to your loved one.

· Talk about it: Expressing your feelings to others can help come to terms with the loss.

· Journaling where you write about your feelings can also help.

· Some people find it helpful to talk to a therapist. It is important to note that there will be times when you do not want to talk about it and that too is ok.

Aspects of Counselling/Therapy that may be helpful

· Being listened to in a non-judgmental way.

· Simply speaking/narrating the story of the loved one to someone in a safe place.

· Having a space to talk about the struggle of loss.

· Clients often have regrets and sadnesses surrounding the loss and counselling and therapy can allow space to be heard.

· Counselling can show how our reactions are normal reactions to loss.

· Therapy is a space where you can learn not to forget your loved ones but instead how to live without them.

· Within therapy there is an opportunity to learn about what you are going through and how to process your emotions around the loss.

· Families can also benefit as it can facilitate or allow discussion about the loss.

· Therapy can also facilitate rituals and the creation of ways to remember the loved one thus allowing for greater processing of the loss.

Finally, the death of a loved one may mean facing some difficulties and making challenging decisions. There may be financial decisions to make, and this can be overwhelming, especially in the immediate aftermath of the loss. Try, if possible, to hold off on any major decisions in the first twelve months after the loss. If a decision must be made use your support network to help, make a balanced decision that will offer the best options for you.

Remember to be kind to yourself in your changed world.

References:

Attig, T. (2001). Relearning the world: Making and finding meanings. In Meaning reconstruction & the experience of loss. (pp. 33-53). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10397-002

Bonanno, G. A., & Kaltman, S. (2001). The varieties of grief experience. Clinical Psychology Review,, 21(5), 705-734. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00062-3

Gillies, J., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2006). Loss, Grief, and the Search for Significance: Toward a Model of Meaning Reconstruction in Bereavement. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 19(1), 31-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720530500311182

James, J. W., & Friedman, R. (2009). The Grief Recovery Handbook, The Action Program for Moving Beyond Death, Divorce, and other Losses, including health Career and faith (20th Anniversary Exoanded Edition ed.). Harper Collins.

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1992). Shattered assumptions: toward a new psychology of trauma. . The Free Press.

Klass, D., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. (2014). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor & Francis.

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2006). Complicated Grief: A Conceptual Analysis of the Field. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, 52(1), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.2190/d1nq-bw4w-d2hp-t7kw

Stroebe, M. S., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Studies, 23, 197-224.

Wilson, J. (2014). Supporting People through Loss and Grief. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Worden, J. W. (2010). Grief counselling and grief therapy : a handbook for the mental health practitioner (4th ed.). Routledge.